Robot Corporations

Why the Norfolk Southern train crash was not just an accident. It was the most likely outcome.

Ever since people were invented, we've been questioning their purpose. Like, why are they here, and why do they have a relentless hunger for sex and food? And why do they dominate the animals, but only sometimes? For example, Sharks. They'll make us their dinner in a heartbeat. And dogs – they'll make us make their dinner. Sometimes it's hard to know who's in charge.

Still, when it comes to language and weapons, humans are by far the dominant species. Even a primitive invention such as the javelin has led to the invention of both steakhouses and nuclear weapons. Two of the most powerful forms of dominance. The ability to destroy a city and eat a ribeye cooked your way on demand. I dare the dog to even try to do that.

Full disclosure, the writer of this article is a person who wonders about its purpose just as much as the next one. I say that because it's not a given. It's hard to say how much time I have before I'm replaced by Bing's new search engine. With AI creeping into every space we writers used to haunt exclusively, you never really know who or what you're reading. Or whether it's reading you back.

Ever since AI started stealing our jobs, we've been questioning all the more. Where did I come from? Why am I here? Why am I prone to failure? Did you check to see if I was plugged in, or maybe try restarting?

Some say a human is no more than a series of chemical reactions, interacting within itself and with its surroundings—consistently presenting predictable patterns, such as how poverty and power both end up yielding corruption. We say we have free will, and yet these patterns consistently present themselves. Whether you have it all or have nothing, it will inevitably bring out the worst in you.

We've been talking a lot about artificial intelligence over the last few weeks, and it feels like technology is at an inflection point. The lines of human distinction are being blurred by a computer that is almost like one (but without tan lines). But artificial intelligence is not a new creation. Artificial intelligence has been a part of our daily life for a long time. We like to call them corporations.

Corporations, at a large scale, are more similar to an operating system than a person. They make decisions, and they're always hungry, but everything fits into the confines of a system. Like a robot, it simply does what it is programmed to do. Like a locomotive, there is no way to stop it.

Let's take a look at Norfolk Southern. It has something like 20,156 employees and earned $12.74 billion in revenue in 2o22. Its purpose is transportation, which they do by managing trains and tracks, managing supply chains, and ultimately making a profit by increasing revenue and minimizing expenses.

I'd like to explain why the train, which derailed in Palestine, Ohio, spilling tons of hazardous waste, was not just a catastrophe, but it was in the budget. It was part of the operating system.

It's a matter of debate whether a corporation is a person or an inanimate entity; to determine that, we would need to define "person.” Let’s start by looking at the US Federal Statutes:

In determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, unless the context indicates otherwise—the words "person" and "whoever" include corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals;

In other words, we're all people, whether we're a business or not. But we are not businesses, and businesses are not us unless the context indicates otherwise. Here's how Wikipedia explains it.

This federal statute has many consequences. For example, a corporation is allowed to own property and enter contracts. It can also sue and be sued and held liable under both civil and criminal law. As well, because the corporation is legally considered the "person", individual shareholders are not legally responsible for the corporation's debts and damages beyond their investment in the corporation. Similarly, individual employees, managers, and directors are liable for their own malfeasance or lawbreaking while acting on behalf of the corporation, but are not generally liable for the corporation's actions.

What this means, if I understand it correctly, is that artificial intelligence can be held liable for its malfeasance, but the programmer who created it or owns it may not be liable beyond their investment in it. Of course, take this with a grain of salt because Wikipedia is just a person, and nobody's perfect.

We tend to assign moral intent to corporations, identifying them as predatory or greedy. But this idea suggests a sentient state that does not really exist. Whether they are a person or not, corporations are, in essence, artificial intelligence programmed to work within a specific operating system.

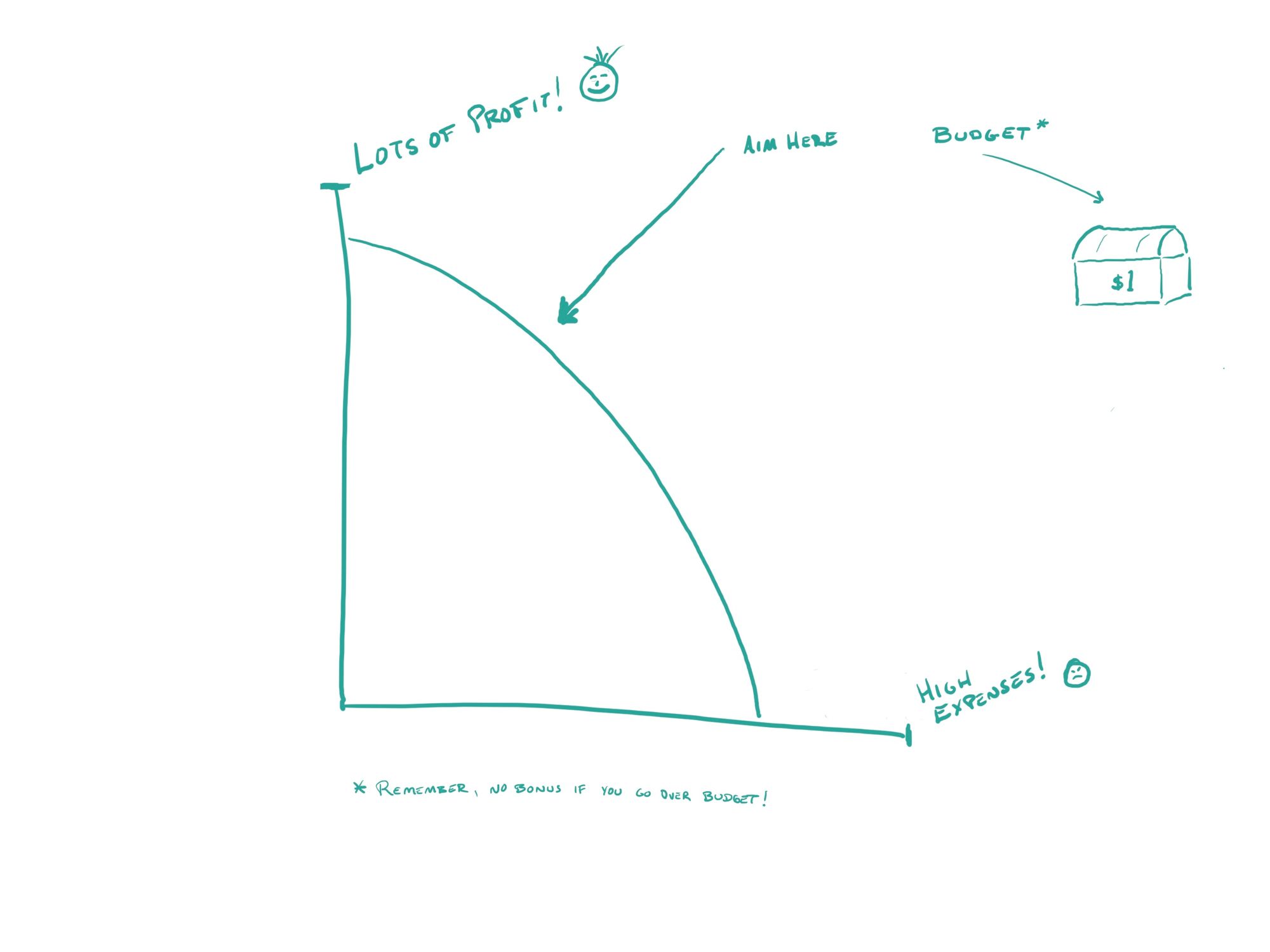

To break it down into simple terms, a corporation is run by something similar to a spreadsheet. Each row has a function. Each column is a list of options. Single fields have 'if-then' equations, and the system performs accordingly.

Put simply, an Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainee in Hammond, IN, only does what an Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainee in Hammond, IN, does, and that happens in the context of the Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainee's department, perhaps narrowed down to a region or a unit. Their job is to do something related to electric signals and to get it done on time.

To me, it sounds like a fairly simple job. I imagine it like pushing a button at certain intervals. Maybe pulling a couple of levers. Then, twisting some wires and probably drinking some coffee.

When you have 20,156 of these people with different titles, including Senior Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainee, the corporation creates systems to manage the countless functions that take place to accomplish its goals.

In other words, it has an operating system and follows the program. It does no more and no less. It's possible it could have a line of code with a bug (also known as a bad employee or some system that doesn't work). Outside factors could increase or decrease its performance or create roadblocks, but the program addresses this by navigating them with the core purpose of increasing revenues and minimizing expenses.

This is especially the case as the organization grows. When there are multiple investors and thousands of employees, each department is acting within its framework of control over limited functions, following the imperatives set before them. Decisions are made in the context of each department's narrow dominion.

Accounting departments manage the books. Logistics departments source and ship things. The sales department drives new business. Marketing drives the brand. Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainees push buttons and twist wires. The larger this organization gets, the more each one of those departments divides into focused subgroups over functions within functions. Sometimes, with no direct awareness of the day-to-day of any other department.

When you break it down, each department's responsibility is to "do better" with a limited set of levers to pull.

Doing Better

In the late 1700s, Scottish Enlightenment thinker Adam Smith introduced a metaphor of an invisible hand. The idea says that a free market yields the best benefit for the whole society because when people act in their own self-interest, they produce an unintentional and widespread benefit.

The butcher and the baker will have to provide quality meat at an affordable price to keep people coming back and buying their goods. The customer will need to contribute labor to the market to afford the meat. Competition will keep their prices under control. They are guided by an invisible hand rather than the visible one of a regulated market.

It sounds wonderful. Especially if there's a butter churner next door to the butcher. But Adam was forgetting that butchers are carnivores.

Inevitably, Adam's friend, Mr. The Butcher, is going to source his meat from the most economically efficient production options, which probably involves cows that are fed steroids and corn, and don't get a lot of exercise, so long as the consumer is none the wiser. Eventually, he's going to buy the baker's business and do the same thing. Decrease expenses. Sell more Steak. And now bread.

When the corporation considers labor and operations costs, everything is subject to a measure of impact. In the same way that the butcher accepts a certain amount of loss to ensure it can capture all possible revenue, the train operation will do the same. In the context of that corporation, the accounting manager, the business developer, and the Electrical Apprentice Signal Trainees will too.

When you have 20,156 people involved in the process, each person becomes part of an algorithm with an "if-then" statement guiding its assignments. If-then statements are a concept of computer programming. If [input] happens, then conduct [output] in response. Each department is a measure of output with goals, discrete missions, and on-off switches. Their decisions are influenced by a series of micro and macro incentives and cost-benefit analyses. At scale, departmental decisions become part of tiny automations inside an enormous robot, responding to inputs and producing outputs.

Is it more costly to replace bearings more often? Or should we just pay the cost of occasional losses and fines? When the cost of cleaning up a chemical spill is in the millions and stock purchases to benefit the corporation are in the billions, the cost-benefit analysis presents itself quite clearly on the spreadsheet. The decision is obvious. It's cheaper to focus on revenue and accept some loss.

Pay the fines. It's cheaper.

We should expect nothing less than for a corporation to act as it is programmed to act. For a corporation, its purpose is never to destroy people. Its purpose is to deliver a return for its investors. To respond to its inputs and produce its outputs. In each department, the purpose is to operate at peak efficiency. To do better. And the free market, at its best, will do just that. Like a robot, it doesn't have feelings. Like a locomotive, there is little you can do to stop it. Some day, it will derail. It's already in the budget.

A train derailing, a chemical spill, the cost of cleanup, and the cost of the fines. It's not a long shot. It is the most likely outcome. And that's a feature of a free market.